What are the benefits of providing training to maintenance personnel?

Employees at world-class organizations spend as much as 10 per cent of their time engaged in training and education. But in a recessionary environment, training is often one of the first activities to be cut.

January 11, 2017 | By Rehana Begg

Jeff Smith, a reliability subject matter expert, and Mark Barnes, vice president of Reliability Services, Des-Case Corporation, have distinct points of view on the benefits of training and why companies should invest in their employees.

Jeff Smith – Emphasize the right training

Jeff Smith is a reliability subject matter expert and served on the U.S. tag for ISO 55000.

In many industries I see training for the sake of training, meeting that key performance indicator (KPI) so we can retain our training budget. The training provided in this environment is often aligned with what the most convincing salesman has to provide. So, before I embark on a discussion praising the virtue of training, I would like to emphasize that it should be the right training.

The correct training for maintenance personnel is not only machine/tool specific but also meets the objectives of the organization. So you hire a new tradesman who has a trades ticket from a governing body and you can assume he has some basic skills. Then, as a world-class organization you do the following:

- Conduct a skills gap analysis to identify the training program required for his/her individual skillset.

- Design a development program to ensure their skills will be enhanced over time.

- Train them in the workflow business processes, including work-order feedback.

- Teach them the expectations of your site’s safety, environmental and health programs.

- Train them in your frontline reliability expectations, including preservation of evidence, five why, short interval control, etc.

- Ensure they understand your failure registry program (FRACAS).

Now if your organization lacks maturity in the reliability world, for example, you have poor work packages with little follow-up, then you need this new tradesperson to be a true master craftsman to be successful. If you lack targeted training and supporting systems you are people dependant. If you run a people-dependant organization you need great people. Even great people leave your organization, so you need succession planning, which puts us back to training.

Sustainability is only attained by transferring skills. This requires a focused competency based learning program. To attain competency requires three phases of learning: educational, cognitive and experiential.

Educational: The educational component is the point most companies deliver with the assumption that the learnings are retained. Various studies have shown that in a classroom environment students will only retain from 5 to 25 per cent of the content covered and this is influenced by the type of learner they are. The three learning types are:

- – Auditory learners (hear) – They prefer to listen to explanations.

- – Visual Learners (see) – They learn best by looking at examples or demonstrations

- – Kinesthetic learners (touch) – They process information through hands-on experiences

All people tend to have somewhat of a combination of the three types of learning. Optimized educational training attempts to address the three learning types to maximize the knowledge retention from the educational component of training.

Cognitive: Though the educational part of learning is foundational, the majority of skills development happens in the cognitive phase of learning. This is the point at which the student is actually conducting the skill and an experienced person is mentoring them through the tasks. This component of skills development covers around 70 per cent of the learning and is essential to skills retention. There are multiple methods to provide cognitive mentoring from onsite partnering, in-house transfers (the trainee is reassigned to work under a competent mentor) or remote monitoring (work is remotely peer reviewed and guidance provided).

Experiential: The experiential component of training is a product of application of the skills. There will be a point where the student has applied the skill a multitude of times and may have developed an individual approach or solved unique challenges. This is the point at which the student has developed the skills to become a subject matter expert and has earned the knowledge to become a trainer.

Barnes comments:

Jeff, I think you’re absolutely right. Too many companies provide training to simply “check a box” without making it part of a strategic initiatives. Particularly with today’s generation who tend to learn more by “doing” than “listening,” the importance of the cognitive and experiential components to training will become increasingly important.

Mark Barnes – Distinguish between training and education

Mark Barnes, PhD, CMRP, is vice president of Reliability Services at Des-Case Corporation

Jeff, I think you’re absolutely right. Too many companies provide training to simply “check a box” without making it part of a strategic initiatives. Particularly with today’s generation who tend to learn more by “doing” than “listening,” the importance of the cognitive and experiential components to training will become increasingly important.

While it’s hard to argue that training employees isn’t a good thing, I think we need to draw a distinction between training and education. In my mind, training is about teaching someone how to perform a specific task or use a specific tool or instrument. For example, if your organization has invested in a new laser alignment tool or ultrasonic leak detector, training a mechanic or millwright how to properly use the tool to achieve the desired result is of paramount importance. Where most companies go wrong in my opinion is with basic education. Whereas training provides the “how,” education provides the “why” and done incorrectly, education can actually have the opposite effect from what was intended.

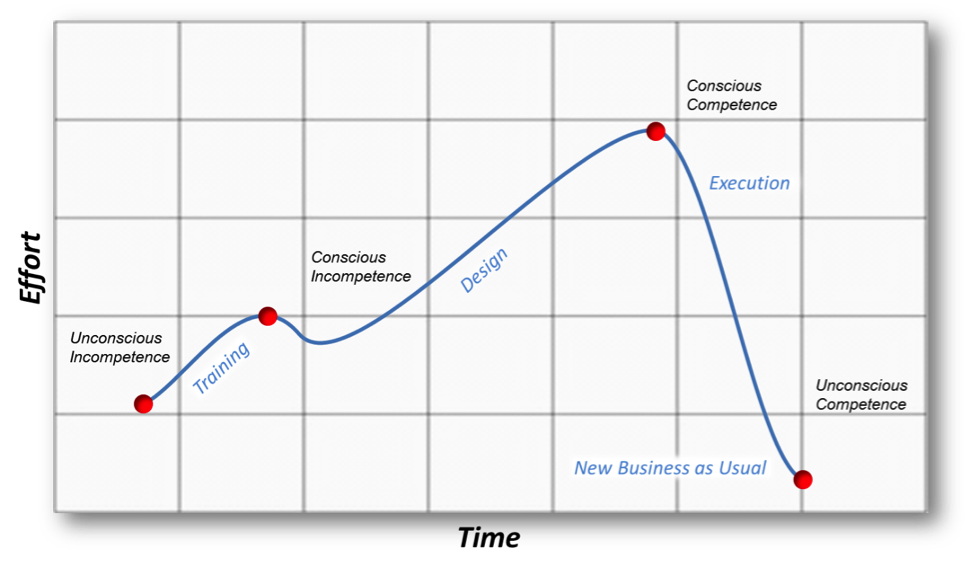

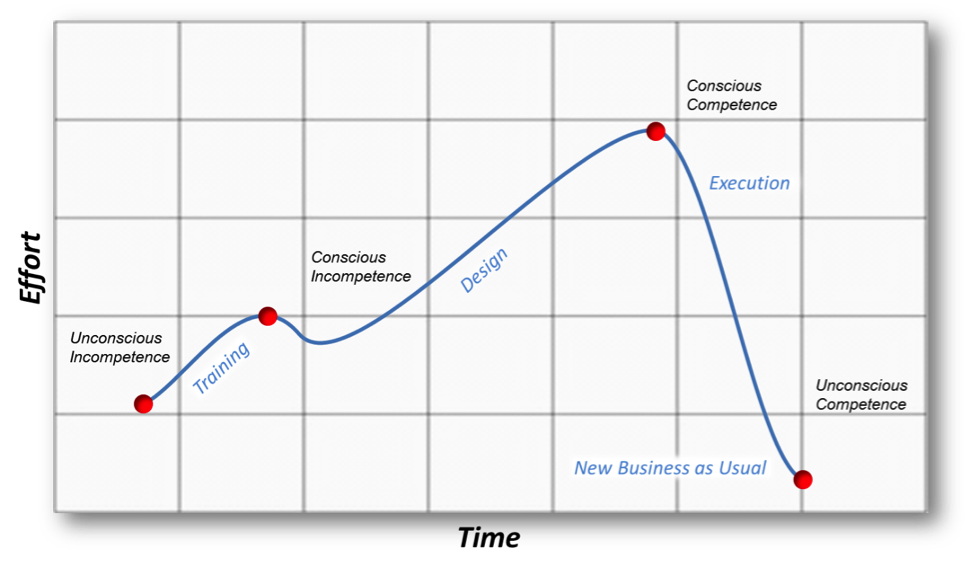

To illustrate my point, we need to understand how training and education plays into overall organizational change (Figure 1). When companies embark on a new business process, companies transition through four distinct phases of organizational learning. At the beginning, most organizations exist in a state of “unconscious incompetence.” Unconscious incompetence simply means that people within the organizations are behaving in a certain way, not because they are consciously thinking about their actions, but are simply doing their job the way they were told or trained to do so, often based on tribal knowledge.

Figure 1: States of Organizational Learning. Ref: Learning to Fly Chris Collison & Geoff Parcell, Capstone Publishing, 2001).

Often as a result of crisis (a catastrophic failure), an epiphany (for example attending a conference and hearing a particularly inspirational speaker) or a corporate mandate to lower costs, training (or more correctly education) is scheduled to bring awareness to the situation. I’ve presented countless educational classes where my mandate was in essence to tell a group of hardworking millwrights that everything they’ve been doing for the past 20-30 years is wrong! It’s about taking a group of individuals who are unconsciously incompetent and helping them get to the point of conscious incompetence!

Conscious incompetence simply means that people are now aware that certain practices or processes are sub-optimal. But the day they exit the classroom, usually nothing has changed. The plant is still performing the same tasks poorly, using the wrong tools and the wrong procedures. The only difference is they now know they’re doing it wrong! Conscious incompetence is a difficult place to be. While some take it as a rallying cry – a call to action – others let it consume them, feeling blamed for things that are truly beyond their control.

When organizations fail to recognize the danger of conscious incompetence, eventually they slips back into the same old “business as usual” but now they often adopt an air of cynicism. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve heard: “my boss needs to hear this” or “things will never change around here.” In my experience over 50 per cent of companies that conduct educational sessions fall into this category, never executing on the changes necessary to move on from being consciously incompetent. For some employees, the response is to adopt a “punch the clock” mentality with poor drive and motivation. But for those that take this to heart, it’s a dangerous situation for any employer. Frustrated by knowing they’re performing sub-optimally without being given the tool and support necessary to make effective change, driven employees may in fact elect to find new career opportunities where their dedication and new-found expertise are better appreciated. In this case, education has had the opposite effect.

Organizations that truly manage to effect lasting change use education to motivate leaders at all levels of the organization to be a part of solution. Through hard work, commitment and most importantly management support to provide the financial and human resources to effect change, companies that have truly embraced the need for change ultimately get to a point where they are consciously competent, we’re still having to think hard but have sufficient resources in places that things are starting to get done to right way across the organizations. Once conscious incompetence is reached, it’s a short downhill ride to unconscious competence. In essence we’re doing things the right way, but not having to work or think harder. In fact, oftentimes the new business as usual is easier, which is a key component in making to new practices sustainable over the long haul. Organizational change such as that illustrated in Figure 1 cannot occur without education. By the same token, it needs to be part of a bigger strategy, otherwise it’s of little value. Good education is invaluable but needs to be almost evangelical in nature: inspiring and motivational, not just death by PowerPoint.

Smith comments:

Many of the issues Mark mentions are related to executive sponsorship. The training logic required for maintenance is no different than the training required for a new VP. What skills does he have, what skills are required for the roll, and how do we address the gaps? Training in maintenance and reliability practices needs to start with the C-suite and be understood by the whole organization. Lack of understanding leads to lack of sponsorship, and once again the right training/education is the answer.

Mark Barnes, PhD, CMRP, is vice president of Reliability Services at Des-Case Corporation. Barnes has published more than 100 articles and several book chapters on lubrication and oil analysis. His PhD is in analytical chemistry. Reach him at mark.barnes@descase.com.

Jeff Smith is the reliability subject matter expert for Acuren. Smith has served as senior advisor for the Association for Maintenance Professionals (AMP) and served on the U.S. tag for ISO 55000. Reach him at jsmith@acuren.com.