Maintenance Case History: Outsourcing is key strategy for maintaining water filtration plant

Across from the Island of Montreal, giant electric and diesel motors ranging up to 950 hp pump an average of 170,000 cu m of water a day from the St. Lawrence River into two filtration plants and onwa...

September 1, 2001 | By Carroll McCormick

Photos: Carroll McCormick

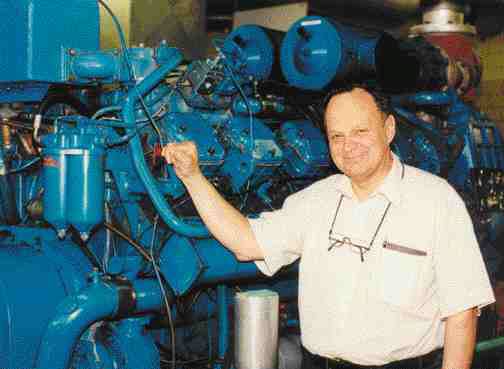

Photos: Carroll McCormickJohn Brown has been the foreman in the Longueuil water treatment division since 1985.

Across from the Island of Montreal, giant electric and diesel motors ranging up to 950 hp pump an average of 170,000 cu m of water a day from the St. Lawrence River into two filtration plants and onward to 250,000 residents of four South Shore cities. In Quebec, Longueuil’s water filtration system is exceeded in size only by Montreal’s own water filtration facility.

It seems counterintuitive that the Longueuil water filtration division does not have a small army of maintenance workers. Rather, it depends on a small team of in-house specialists, several small but well-equipped parts and repair shops, and expertly handled maintenance outsourcing.

“Presently, we don’t have enough work to keep more maintenance personnel going,” says John Brown, the water filtration division’s foreman. He adds, “We keep personnel to a minimum because it cuts expenses.”

Brown is well-connected with specialized companies that do yearly inspections of his equipment and who are generally available around the clock for service calls. He employs a variety of techniques learned over the years to make sure he is getting quality, value and reliability when he outsources.

The equipment

Water is drawn from near the riverbed almost directly under the Jacques Cartier Bridge. It is pumped through a lift station equipped with five 650-hp water pumps with a capacity of 15 million gallons a day, as well as a pair of 300-hp pumps with a capacity of 7.5 million gallon a day. An optimum combination of 650-hp electric motors, 650-hp diesel motors and a 300-hp electric motor is chosen satisfy the demand on any given day, no more; some serve as backup equipment.

The water flows to two filtration plants: the Longueuil Local Filtration Plant (LFP), a facility built in the 1940s with a 40,000 cu m daily capacity, and the Longueuil Regional Filtration Plant (RFP), which came on stream in 1956 to provide an additional 300,000 cu m of filtered water capacity daily.

Other facilities in the system include a 45,000 cu m reservoir and an Industrial Park Pumping Station, which supplies unfiltered water to a nearby industrial park.

A maintenance mechanic performs regular inspections and general maintenance of everything outside the RFP. Inside the RFP, which has the most and the largest pieces of equipment of all the facilities, the mechanic handles the maintenance, but operators are responsible for inspecting the equipment.

The RFP electric motor room has four gigantic, 750-hp, 2300-V electric motors, driving pumps delivering 790 litres of water a second. They were manufactured in Lachine, Que., by a now-defunct company called BBC Brown Boveri. Three 780-hp, V12 bi-turbo Dorman diesel engines, manufactured by English Electric Diesels Limited, stand ready to drive backup pumps. A 780-hp V-12 monster diesel and a smaller, 130-hp diesel, with capacities of 450 kW and 75 kW, respectively, stand ready to run a backup electrical generator for the RFP.

The RFP operators do a daily pump inspection that takes about an hour. “If ever there is anything wrong, the inspector fills out a defect sheet,” says Brown. “They give it to me and we dispatch it right away to our maintenance mechanic.”

The work

A control instrument technician is responsible for keeping the extensive amount of control equipment in the RFP in good repair. A water quality technician is responsible for anything related to the quality of the water. They work from a weekly inspection and calibration checklist that takes about two days a week to complete. The rest of their time is spent on daily inspections and repairs.

“We have a repair shop and spare parts, but just for the basic repairs,” says Brown. There is a spares room and repair bench for control equipment, and another spares room for larger parts. For heavy mechanical repairs the RFP has a well-equipped repair shop that contractors can use. “I don’t like to let the equipment go out to be fixed,” says Brown.

The water quality technician doesn’t do the repairs, says Brown. “He just makes sure equipment such as water turbidity meters and chlorine analyzers are functioning according to the established norms. That’s the basic everyday maintenance. If something goes wrong we call the company that supplies the equipment.”

Lessons learned

Years of contracting out have taught Brown important lessons. Keep more than one contractor per specialty, if possible. “Once we had a contractor go bankrupt,” he says. Getting references from bidders — jobs over $5,000 must be put to tender — is a good way to ensure that the low bidder is capable of doing the job. “We had one company bid lower than the rest to replace three impellers. We were a bit afraid, but we checked with the other companies that used him and they were very satisfied.”

On the flip side, however, Brown says “It is very specialized work. Every once in a while, someone bids who cannot do the job.”

The impeller job reminds Brown of another trick: The contractor who swapped out the first of the four impellers that needed replacement thought he had the job sewn up for the next three and bid high. He lost the contract.

He has also caught contractors gradually raising their rates over several months, thinking Brown was not paying attention. “I validate my prices all year long and every six months I check competitors’ prices.”

Contributing editor Carroll McCormick is based in Montreal.

Living in the water world

“I have been in the water world since 1969,” says John Brown, who is a water treatment technician by trade. After a stint as superintendent in the water filtration facility in Huntington, Que., he took the job of foreman in the Longueuil water treatment division in 1985.

About six years ago he attended night school to earn a certificate in management offered by the University of Montreal. He chuckles fondly about the frequent pleasure of meeting his daughter, who would be heading home from classes just as he was showing up for his.

Brown’s nominal title is that of foreman, but his job description reads more like that of a supervisor. His duties include taking care of maintenance, the budget, holidays and personnel. “When I applied for the job of foreman, I thought it would be a really nice job. But then I found out that there (was a) lift station, a regional filtration plant, a local filtration plant, a booster pump station, two 5-million gallon tanks and an industrial park pumping station.

“The challenge was really good. It was always my big dream to come back to a big town.”